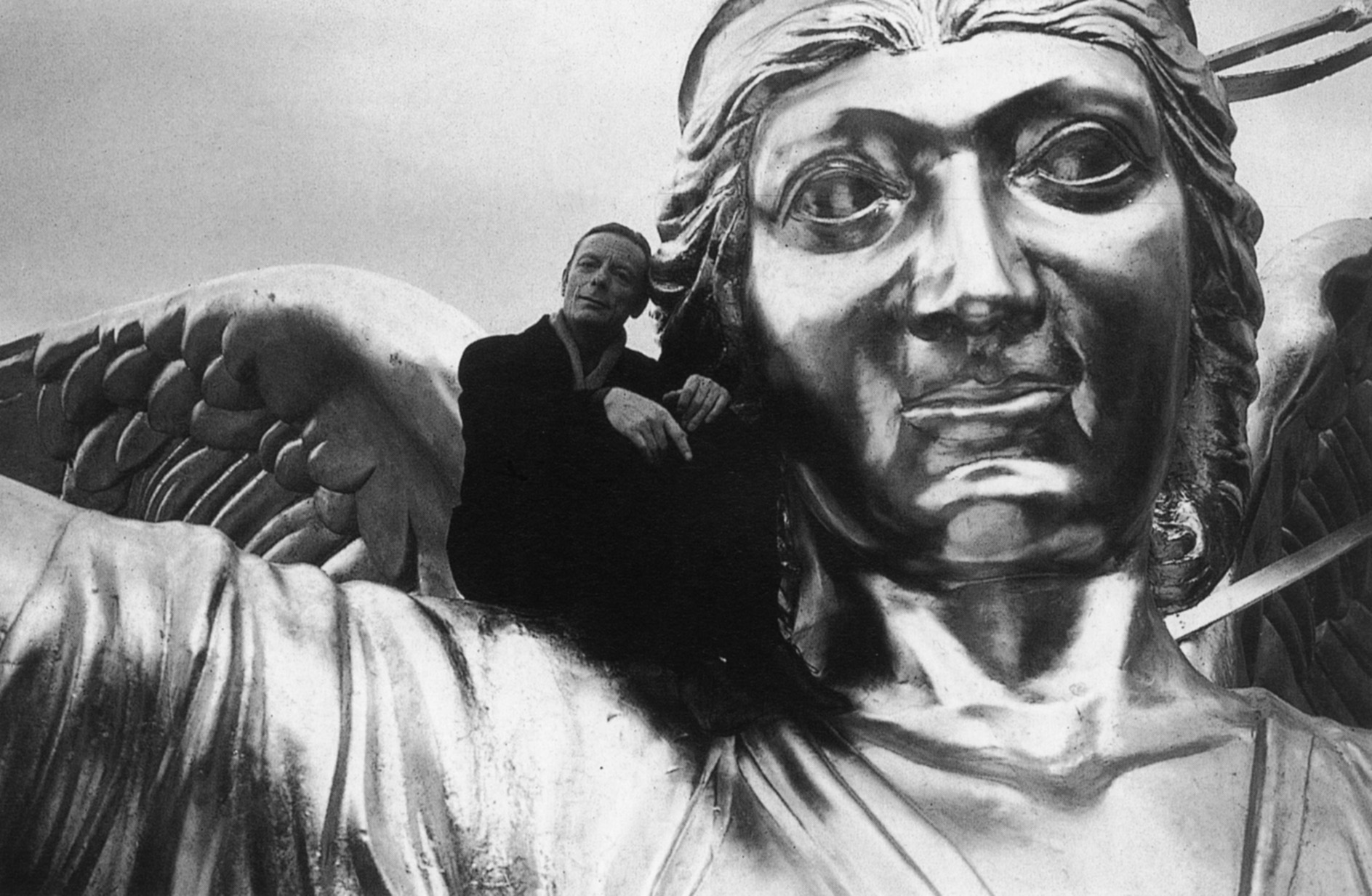

Still a street-fighting man

In his first interview with an English newspaper, 83-year-old Portuguese novelist José Saramago reveals that his famed radicalism is undiminished

Stephanie MerrittSunday April 30, 2006The Observer

The architecture of José Saramago's purpose-built library, as it rises from a parched hillside on his adopted island of Lanzarote, creates the impression of a modern cathedral. Sunlight splinters through high, narrow windows of opaque glass that stretch the full two storeys; the clean, white walls and cool flagstones contribute to a sense of hushed reverence in the presence of so many volumes, ancient and modern, in so many languages. Here is a shrine to literature, an alternative religion for a Portuguese Nobel laureate, who left his homeland 14 years ago in protest at the government's censorship of his novel, The Gospel According to Jesus Christ (it vetoed its submission for the European Literature Prize on the grounds that it was offensive to Catholics). It takes some effort to believe that Saramago is about to turn 84 - not just because of his vivid physical presence, his barely-lined face and the quickness of his eyes and hands when he talks, but also because of his extraordinary productivity.

Although Seeing is published this week in English translation, he has produced another book in the meantime; Las Intermitencias de la Muerte was published last autumn in Portugal, Spain and Latin America (his Spanish wife, Pilar del Rio, translates his books as he goes along so that they can be published simultaneously for his large Spanish readership), and he is now working on an autobiography entitled Peque?Memorias (Little Memories), about his childhood in rural Portugal.

But the image of the venerable novelist shut away in his island retreat, disengaged from the world, could not be further from the truth. Saramago is about to leave Lanzarote for two months of travelling, as he does most years, in part to promote the new novel, but mainly to speak at conferences and presentations on politics and sociology. 'Most of it doesn't have much to do with literature,' he explains, 'but this is a part of my life that I consider very important, not to limit myself to literary work; I try to be involved in the world to the best of my strengths and abilities.' Still a member of the Communist party, Saramago is a vocal opponent of globalisation and many of his best known novels have taken the form of political allegory. Does he believe that the artist is obliged to take on a political role? 'It isn't a role,' he says, almost sharply.

'The painter paints, the musician makes music, the novelist writes novels. But I believe that we all have some influence, not because of the fact that one is an artist, but because we are citizens. As citizens, we all have an obligation to intervene and become involved, it's the citizen who changes things. I can't imagine myself outside any kind of social or political involvement. Yes, I'm a writer, but I live in this world and my writing doesn't exist on a separate level. And if people know who I am and read my books, well, good; that way, if I have something more to say, then everyone benefits.'

Seeing evolved into a kind of sequel to his 1995 novel, Blindness, in which the inhabitants of a republic that may or may not be Portugal are struck by a temporary epidemic of blindness and quickly revert to barbarism. Seeing revisits the same country four years later as it experiences another unprecedented phenomenon: despite the high turnout for the municipal election, when the votes are counted, more than 80 per cent have been returned blank. This wholesale vote of no confidence in any of the political parties makes a farce of the democratic process and the leaders are forced to declare a state of emergency.

'I was giving a talk about my novel, The Double, in Barcelona,' Saramago remembers. 'I have this habit of only talking about my books for a few minutes, then I prefer to spend the time talking about the world in which we find ourselves, a world which is a disaster, and usually I end up talking about the problem of democracy, whether we truly have a democratic system, and I believe that we don't. And in Barcelona, someone asked me, well then, what do you propose? Because I was saying that, in reality, the world is governed by institutions that are not democratic - the World Bank, the IMF, the WTO. People live with the illusion that we have a democratic system, but it's only the outward form of one. In reality we live in a plutocracy, a government of the rich.'

So what was his solution?

'I answered that I didn't have a solution, except that we, as citizens, do have the power of the vote, but we always use it to vote for one or other of the parties on off er. But there is another possibility, which is to cast a blank vote.' He leans forward and points a stern finger. 'And this is not at all the same as abstention. Abstention means you stayed at home or went to the beach. By casting a blank vote, you're saying that you understand your responsibility, you have a political conscience and you came to vote, but you don't agree with any of the existing parties and this is the only way you have of saying so.

'Then I thought about what would happen if the blank votes went up to 50 or more per cent. It would be a way of saying society has to change but the political powers we have at the moment are not enough to effect this change. The whole democratic system would have to be rethought.' He speaks Spanish with a heavy Portuguese inflection, each sentence composed with precision, not at all like the rather breathless, digressive narrative style that has become a hallmark of his novels. Expounding these theories, he comes across as grave and wise, though when he talks about the problems of poverty in Africa or the volatility of most employment, there flares a passionate anger that has fuelled his lifelong commitment to leftist politics.

But there's a twinkle of humour, too, in his mock sternness with his dog as she scuffles around our feet, and a warmth in his exchanges with his wife, who comes in to offer us coffee; as she turns to leave, he impulsively clutches her hand and gives it an affectionate squeeze. I point out that, for all the brave intentions of the blank voters in Seeing, the novel has a bleak end - the authorities simply revert to force, though the protest has been as peaceful as a protest could be; in the end, it seems to have been in vain. I tell him it reminded me of the anti-war demonstrations in London.

'Yes, it all ends badly, because things are not mature,' he says sadly. 'Here in Spain, 90 per cent of the population was against the war and nobody in power was interested. But look what just happened with the employment law in France - the law was withdrawn because the people marched in the streets. I think what we need is a global protest movement of people who won't give up, who won't leave the streets. In Madrid and London, we marched, we did our duty, then we went home and those in power did nothing.

'But we have to keep on demonstrating and demonstrating and demonstrating' - here he breaks into a rich, throaty laugh - 'there's no solution but to say we do not want to live in a world like this, with wars, inequality, injustice, the daily humiliation of millions of people who have no hope that life is worth anything. We have to express it with vehemence and spend days on the street if we have to, until those in power recognise that the people are not happy.'

In a lifetime of political activism, Saramago has witnessed the struggle from various angles. He grew up as the son of landless peasant labourers in a village north east of Lisbon and, although he published his first novel, Land of Sin, at the age of 23, it was another 30 years until he attempted another. In the meantime, he worked successively as a mechanic, civil servant, metalworker, production manager at a publishing house and a newspaper managing editor, until the politico-military coup of 1975 made it impossible for someone of his political colours to find work.

He turned to writing full time, publishing his second novel, Manual of Painting and Calligraphy, in 1976, and producing plays, poetry, essays and newspaper columns until his 1982 historical novel, Baltasar and Blimunda, brought him international recognition. His most successful novels were all written when he was in his sixties and he won the Nobel Prize in 1998, at the age of 76. Why, after so many years and excursions into different genres, did he decide that the novel was the best form for the ideas he wanted to express?

'I think the novel is not so much a literary genre, but a literary space, like a sea that is filled by many rivers. The novel receives streams of science, philosophy, poetry and contains all of these; it's not simply telling a story.' Saramago is often described as a pessimistic writer. I ask if he feels genuinely pessimistic about the future or if he thinks there could be hope for the left?

'We're not short of movements proclaiming that a different world is possible,' he says, heavily, 'but unless we can co-ordinate them into an organic international movement, capitalism just laughs at all these little organisations that do no damage. The problem is that the right doesn't need any ideas to govern, but the left can't govern without ideas. It's very difficult.

'At 83, I don't hope for much, but you are young, you have to keep a perspective. I don't think this novel is going to change the world, but look - those in power are there because we put them there. If they don't get it right, then out! And let others try. There are plenty of reasons not to put up with the world as it is, and if the book has any kind of message, I suppose that's it.'

|