A propósito do trabalho de Philip Roth, um artigo no The Guardian:

The long road home

An intensely private man, Philip Roth is one of America's greatest writers. He is dedicated, even obsessive, about his work but loathes the fame that attends it. After spells in eastern Europe and the UK, his return to New York marked a period of creative renewal as he reflected on the US through the lens of history. His latest novel revisits - and reimagines - his childhood

por Al Alvarez, Saturday September 11, 2004 The Guardian.

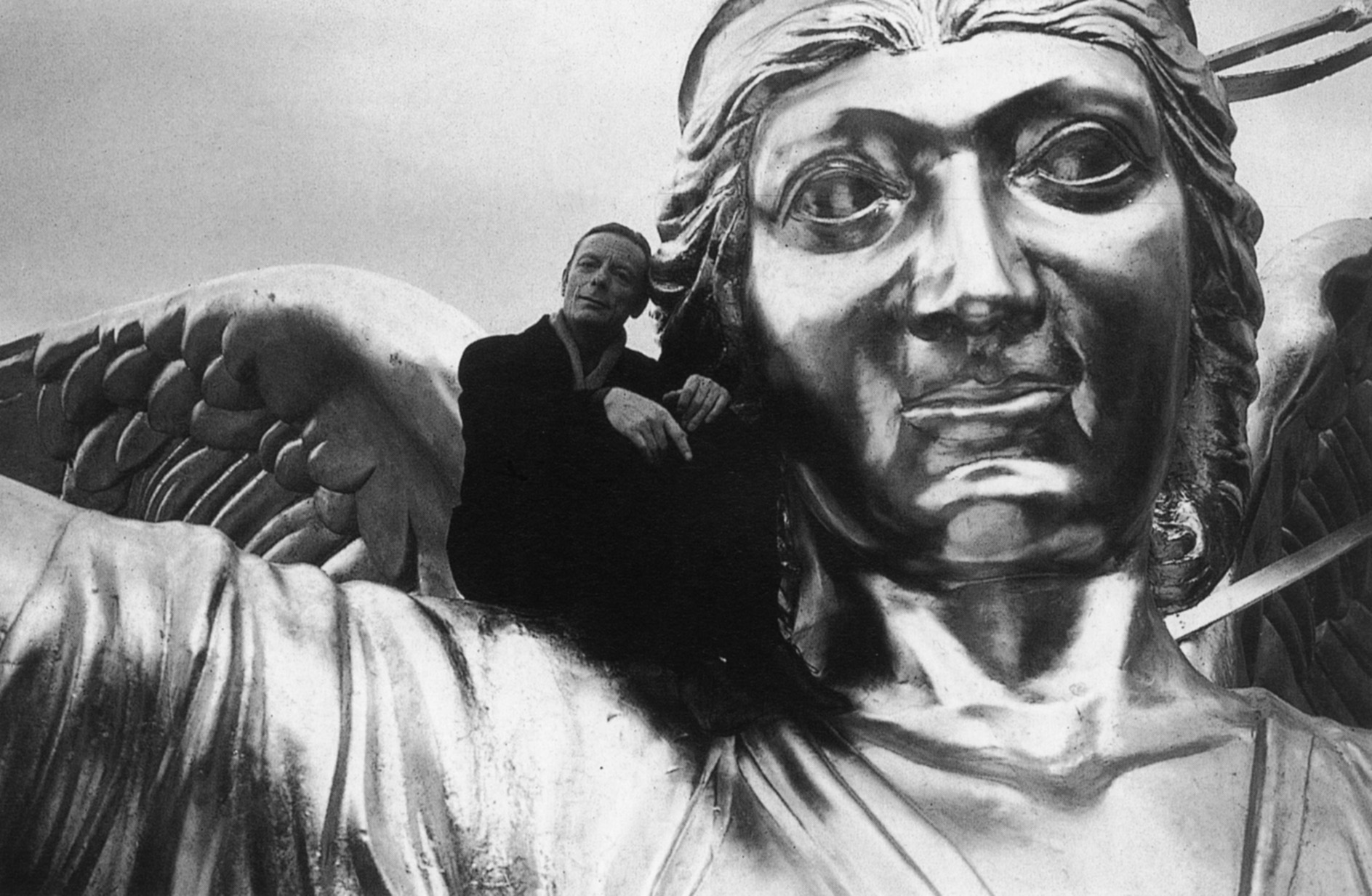

Philip Roth: More powerful and accomplished with age.

Philip Roth has had the grandest prizes available to an American writer, some of them more than once, and he has been to the White House to have the National Medal of Arts pinned on him by former president Bill Clinton. But the honour that seems to have pleased him most is the forthcoming multi-volume edition of his collected works in the Library of America. This officially establishes him as an American classic, with Melville, Hawthorne, James, Fitzgerald and Faulkner, and so far only two other writers - Saul Bellow and Eudora Welty - have been immortalised in this way during their lifetimes.

For the last decade, at an age when most writers are beginning to lose interest, Roth has produced a series of books more powerful and accomplished than any he has written before. And he shows no signs of slowing down.

"Even now, he doesn't relent," says Aaron Ascher, Roth's old friend and editor. "This is a 70-something-year-old writer who is still going uphill and keeps getting better. He has back problems which give him great pain, yet he's always working. He never stops, even in his worst periods."

Roth's face is lined now, his mouth has tightened and his springy hair has turned grey, but he still looks like an athlete - tall and lean, with broad shoulders and a small head. Until recently, when surgery on his back and arthritis in the shoulder laid him low, he worked out and swam regularly, though always, it seemed, for a purpose - not for the animal pleasure of physical exercise, but to stay fit for the long hours he puts in at his writing. He works standing up, paces around while he's thinking and has said he walks half a mile for every page he writes. Even now, when his joints are beginning to creak and fail, energy still comes off him like a heat haze, but it is all driven by the intellect. It comes out as argument, mimicry, wild comic riffs on whatever happens to turn up in the conversation. His concentration is fierce, and the sharp black eyes under their thick brows miss nothing. The pleasure of his company is immense, but you need to be at your best not to disappoint him.

He has always believed in the separation of life and art. He keeps his private life strictly to himself and prefers not to work where he lives. In Connecticut, his studio is back in the trees away from the house; 30 years ago, when he was spending half the year in London, he lived in Fulham and worked in a little flat in Kensington; in New York, there were two apartments on the Upper West Side, one for living in and a studio for work; when he moved more or less full-time to Connecticut, he kept the New York studio and that is where we met to talk.

It is on the 12th floor, a single large room with a kitchen area, a little bathroom and a glass wall looking south across Manhattan's gothic landscape to the Empire State Building, with a wisp of cloud around its top.

The lectern at which Roth works is at right angles to the view, presumably to avoid distraction. Above it is a sketch of an open book, with an indecipherable text that might be in Hebrew, by his friend, the late Philip Guston. There is a bed with a neat white counterpane against the wall, an easy chair in the centre of the room, with a graceful standing lamp beside it, all of it leather and steel and glass, discreetly modern. It is a place strictly for work, spare and chaste, a monk's cell with a great view.

This seems to fit Roth very well. I once asked him what he would like to have been if he could have lived his life again. "A parish priest," he said, "swishing around in a cassock and hearing confessions." He may have missed out on the cassock - he dresses soberly, neutrally, as though not to be noticed - and celibacy is not his style, but in other ways his life is as stern, self-sufficient and dedicated as any priest's: he works long hours, eats sparingly, drinks hardly at all and goes to bed early.

Roth's monkish routine is at odds with what he once called his "reputation as a crazed penis" bestowed on him by Portnoy's Complaint, his great panegyric to the comedy of sex. When Portnoy was published in 1969, it seemed to epitomise the anarchic spirit of the decade. Maybe it did, but the author himself was a product of the 1950s, the last generation of well-behaved, sternly educated children who believed in high culture and high principles and lived in the nuclear shadow of the cold war until their orderly world was blown apart by birth-control pills and psychedelic drugs. Portnoy was considered outrageous when it appeared, but the real outrage was Roth's and he was outraged because he couldn't help being a good boy however much he yearned to be bad.

Like most Jewish families, Roth's was close-knit, affectionate and tempestuous. His father, Herman, was a passionate New Dealer, a forceful indignant man, who worked for Metropolitan Life Insurance Company and rose to be a district manager - which was as high as a Jew could go before Congress passed the Fair Employment Act after the second world war. He and his wife Bess were children of immigrants from eastern Europe and they lived in the largely Jewish Weequahic section of Newark. In those days Newark was the commercial capital of New Jersey, a prosperous industrial town. "I was brought up in a Jewish neighbourhood," he says, "and never saw a skullcap, a beard, sidelocks - ever, ever, ever - because the mission was to live here, not there. There was no there. If you asked your grandmother where she came from, she'd say, 'Don't worry about it. I forgot already.' To the Jews, this was Zion." The neighbourhood schools were good and Roth was a straight A student. He graduated magna cum laude from Bucknell, an idyllic little college in Lewisberg, Pennsylvania, got his MA from the University of Chicago, did a spell in the army, was invalided out with a spinal injury, returned to Chicago to start a PhD and teach freshman English, then dropped out after one term. Ascher first heard of him when his sister, a student at Chicago, wrote to tell him she had sublet an apartment from "a guy called Philip Roth. He says he's a writer."

It was a long time, however, before Roth began to write about the world he was brought up in. Neither of his devoted, sensible parents seems to have had much in common with the comic nightmares that tormented Portnoy and they only began to figure large in their son's work after they died. His new novel, The Plot Against America, is, in a way, his memorial to them. When Roth was working on it he told his friend David Plante, the novelist, that he was "writing about his parents in their prime, when their life was at its full and they were dealing with it". Though the book turned out to be about a lot of other things as well, the portrait, according to Ascher, is strong and accurate: "Herman was fiercely what he was - a marvellous, naïve man who loved his children and was perplexed by them. In this new book, Philip puts him in these terrible situations and he reacts exactly as he would have done in real life."

The idea for the terrible situation occurred to Roth when he read in Arthur Schlesinger's autobiography that the right wing of the Republican party had thought of nominating Charles Lindbergh, the celebrated aviator, anti-semite and friend of Hitler, to run for the presidency against FDR in 1940: "I wrote in the margin, 'What if they had?' Then I began thinking about other what-ifs, like what if Hitler hadn't lost? All this was happening when I was a little child - I was born in 1933 - but it is quite vivid to me because the great outside world came into the house through the radio and through my father's reactions to it. So it began to make sense as a novel. One of the reasons I could never write about what our family life was really like was because my parents were good, hard-working, responsible people and that's boring for a novelist. What I discovered inadvertently was that if you put pressure on these decent people, then you've got a story."

Putting pressure on people and facts and his own experience is one of the many solutions Roth has come up with for the problem to which he has devoted his life: how to transform life into art. "I have to have something to do that engages me totally," he says. "Without that, life is hell for me. I can't be idle and I don't know what to do other than write. If I were afflicted with some illness that left me otherwise OK but stopped me writing, I'd go out of my mind. I don't really have other interests. My interest is in solving the problems presented by writing a book. That's what stops my brain spinning like a car wheel in the snow, obsessing about nothing. Some people do crossword puzzles to satisfy their need to keep the mind engaged. For me, the absolutely demanding mental test is the desire to get the work right. The crude cliché is that the writer is solving the problem of his life in his books. Not at all. What he's doing is taking something that interests him in life and then solving the problem of the book - which is, How do you write about this? The engagement is with the problem that the book raises, not with the problems you borrow from living. Those aren't solved, they are forgotten in the gigantic problem of finding a way of writing about them."

His solutions to the problem have taken many forms as well as a large cast of narrators. Deception, for instance, is written entirely in dialogue, like a stage play. Operation Shylock is a find-the-Roth shell-game, with a false Philip pretending to be the true one until neither is quite sure who is who. The technical problem of The Plot Against America was less tricky but equally hard to solve: although it is a Roth book, the Roth who narrates it is aged seven: "Prior to that, I'd had these rich brains telling the story and now I was going to have to look over the shoulder of a child. I never wrote What Maisie Knew and this was What Little Philip Knew. How do I do that without putting on a straitjacket? The answer turned out to be quite simple: if you have one child in the centre of the book, you have a problem, but it goes away when he is a child among children. So once I discovered the other children to act as foils for him I was in the clear. Then I had a child's perspective, but the book is no longer told by a child; it's told by an adult remembering his family when he was a child."

Roth has never been much interested in aesthetic theories and experiment and when he talks about getting a story right he does so, like any craftsman, with a practical understanding of the materials he uses and the techniques needed to get the job done. In The Ghost Writer, the ageing writer, EI Lonoff, tells 23-year-old Nathan Zuckerman, the most disabused of Roth's stand-ins, that he "has the most compelling voice I've encountered in years. I don't mean style... I mean voice: something that begins at around the back of the knees and reaches well above the head." Voice in this sense is the vehicle by which a writer expresses his aliveness and Roth himself is all voice. Style, in the formal, flowery sense, bores him; he has, he once wrote, "a resistance to plaintive metaphor and poeticised analogy". His prose is immaculate yet curiously plain and unostentatious, as natural as breathing. Reading him, it's always the story that's in your face, never the style.

His voice sounds so spontaneous that the lazy reader might suppose he is listening to confession rather than reading a work of fiction. And this, to Roth, is an insult to the labour he puts into his craft. It also links him with the cult of celebrity and that is something he has fought against throughout his career.

"One dreams of the goddess Fame," wrote Peter de Vries, "and winds up with the bitch Publicity." Roth first tangled with the bitch when Goodbye, Columbus provoked rabbis to denounce him as "a self-hating Jew", and he responded by writing Letting Go, the most conventional of his novels, as if to show that he was indeed as serious and worthy as authors were expected to be in the 50s. Being a good boy, however, did not sit easily either with his surreal comic inventiveness or with the troubles he was having in a difficult first marriage to Margaret Williams. When he finally yoked comedy and rage together to produce Portnoy's Complaint, the serious writer again came face-to-face with the bitch Publicity and this time she didn't let him go.

"In 1969, I wrote Portnoy. Not only did I write it - that was easy - I also became the author of Portnoy's Complaint and what I faced publicly was the trivialisation of everything."

Instead of being read as someone playing brilliant games with reality in the tradition of Kafka and Gogol, Roth got scandal, outrage and best-seller celebrity in its most crummy form. According to Ascher, "the attacks were horrible and disheartening, especially from the Jews. He had to cope with the nightmare of a smash hit. It made him angry and defensive, so he closed up. But maybe it did him good. The setback of great success changed and improved him as a writer. Without it, he'd have been different."

Roth's immediate response was to refuse all public appearances and retreat to Yaddo, the writers' colony in upstate New York. Hiding himself away was easy, but disguising that distinctive, compelling voice of his was a trickier problem. His solution was ventriloquism, narrators with everyday lives not unlike his, but who see them differently and transform them into something else: disabused, tough-talking Nathan Zuckerman who sniffs out every weakness and forgives no one; studious David Kepesh, a professor to whom outlandish things happen when he lets himself go, but who loves literature as much as he loves women; a character called Philip Roth whose relationship to the author is a source of mystery for both of them. Roth remarked to me, apropos of President Bush, that born-again Christianity is the ignorant man's version of the intellectual life. Similarly, reading fiction as though it were true confessions is the ignorant man's aesthetics and Roth has made a mockery of it in many ways. The eulogist at Zuckerman's funeral in The Counterlife puts it pompously but well: "What people envy in the novelist... is the gift for theatrical self-transformation, the way they are able to loosen and make ambiguous their connection to a real life through the imposition of talent. The exhibitionism of the superior artist is connected to his imagination; fiction is for him at once playful hypothesis and serious supposition, an imaginative form of inquiry - everything that exhibitionism is not... Contrary to the general belief, it is the distance between the writer's life and his novel that is the most intriguing aspect of his imagination."

In life as in art: a snide academic at a New York dinner party once tried to show his disdain for the famous author by pretending to mistake him for Herman Wouk and taking him to task for the structural weakness of Marjorie Morningstar. Roth, of course, was too smart to be indignant; he just played right along with the game and became Wouk for the rest of the evening.

His most effective escape from New York celebrity was Czechoslovakia and its writers. He stumbled across them inadvertently, when he was on a holiday tour of Europe and stopped off in Prague to pay homage to Kafka. This was in 1972, three years after both the nightmare success of Portnoy and the far greater nightmare that followed the Prague Spring. Through his Czech translator he met blacklisted writers who cleaned windows and stoked boilers for a living while they wrote books that wouldn't be published at home. Their troubles put his into perspective: "They made me very conscious of the difference between the private ludicracy of being a writer in America and the harsh ludicrousness of being a writer in eastern Europe. These men and women were drowning in history. They were working under tremendous pressure and the pressure was new to me - and news to me, too. They were suffering for what I did freely and I felt great affection for them, and allegiance; we were all members of the same guild."

Back in New York, Roth immersed himself in literature from behind the iron curtain. He went every week to a little college on Staten Island to attend Antonin Liehm's classes on Czech culture and edited a series of eastern European fiction for Penguin.

"My life in New York after Portnoy was lived in the Czech exile community - listening, listening, listening. I ate every night in Czech restaurants in Yorkville, talked to whoever wanted to talk to me and left all this Portnoy crap behind. That was idiotic, this was not idiotic. I lived up in Connecticut, where Philip Guston was my friend, and had my east European world in New York, and those were the things that saved me. I think that's why Hemingway lived in Key West; he liked to be in a world that had nothing to do with what he did all day. Fame is a worthless distraction."

Roth's regular visits to Prague continued until 1977, when he was denied an entry visa, and they seemed to bring about a change in his focus as a writer. By then, he was spending half the year in London, but he left in 1989 to be with his father in his final illness and, following the break-up of his second marriage to the actress Claire Bloom, he never went back. It was, he says, a huge relief to be home: "I used to walk around New York saying under my breath, 'I'm back! I'm back!' I felt like Rip van Winkle waking up with a long beard and discovering there'd been a revolution and the British were gone! Being home, being free in my personal life brought a great revival of energy. I felt renewed."

While he was rediscovering America, Roth immersed himself in the modern classics and they reminded him of what American novelists do best: "The great American writers are regionalists. It's in the American grain. Think of Faulkner in Mississippi or Updike and the town in Pennsylvania he calls Brewer. It's there on the page, brick by brick. What are these places like? Who lives there? What are the forces determining their lives? ... I hadn't yet discovered my own place, that town across the river called Newark, and it didn't have any power for me until it was destroyed in the race riots of 1966. Before, it was too pleasant and my family was too decent to write about. Only when the place had been burned down and the families I knew had been exiled did it become a fit subject for inquiry."

The energy released by his return to America culminated in his great, subversive outburst of comic outrage and exasperation, Sabbath's Theatre. The book reads like Portnoy's Complaint retold by a 60-year-old man raging not about sex, but against the injustice and ludicrousness of death, and it was a turning point. Having vented his rage at the prospect of death, and while he still had time, he set about writing an extraordinary series of novels about what it was like to live in the United States in the second half of the 20th century. After his experience in eastern Europe, he now saw the place more sharply through the lens of history.

In the 50s, when Roth was starting out and literature was considered the noblest of all vocations, the best writers responded in an intensely inward way to whatever was going on in the big outside. All that changed, Roth thinks, when Kennedy was assassinated in 1963: "It was an event so stunning that our historical receptors were activated. The stuff that's happened in the last 40 years - the Vietnam war, the social revolution of the 60s, the Republican backlash of the 80s and 90s - have been so powerfully determining that men and women of intelligence and literary sensibility feel that the strongest thing in their lives is what has happened to us collectively: the new freedoms, the testing of the old conventions, the prosperity. That's what I was writing about in the trilogy that followed Sabbath - American Pastoral, I Married a Communist and The Human Stain: people prepare for life in a certain way and have certain expectations of the difficulties that come with those lives, then they get blindsided by the present moment; history comes in at them in ways for which there is no preparation. 'History is a very sudden thing,' is how I put it. I'm talking about the historical fire at the centre and how the smoke from that fire reaches into your house."

Old age and its humiliations, he says, are equally unpredictable. "I think about Hemingway and Faulkner and how it ended for them - tragically, not peacefully in their sleep. Faulkner drank himself to death; Hemingway's body was banged to bits, the booze had saturated him and he couldn't write; he had nothing to live for, so he shot himself. These are lives of torment... I'm not a romantic about writing, I don't want a tormented life and, by and large, I haven't had one. But these guys... I can't stand to think about how they ended."

"Who knew what getting old would be like?" he says. "There may be a biological blinder about age that's built in. You are not supposed to understand until you get there. Just as an animal doesn't know about death, the human animal doesn't know about age. When I wrote that book about my father in old age, Patrimony, I thought I knew what I was talking about, but I didn't really. In this new book I've brought both my parents back in their full flower. The flow of energy in our house was extraordinary."

It was also the atmosphere in which Roth's own special talents began to flourish. When he was a teenager and his older brother Sandy was an art student in Brooklyn, they would meet up with their friends most weekends at the Roth house in Newark: "My mother loved it. Eight or 10 boys, a very mixed bag, but one thing they had in common was tremendous humour. Some of them I still know and they remember roaring with laughter in our house - laughing and eating and laughing. It was a wonderful period, a great explosion of camaraderie. Our subject was the comedy of being between 15 and 20 - comedy located in sex and frustration - lots of longing, little activity. I think that was the incubator for everything."

Maybe it still is, in a ghostly way. "Roth often visits his parents' grave in New Jersey," Plante says. "He stands at their graveside and weeps. Then he begins to talk to them and they answer. Then he starts joking with them, they have these funny, bantering conversations and he goes away feeling better." |