| quinta-feira, julho 14, 2005 |

| Specimen Days - Michael Cunningham |

BOOKS OF THE TIMES; A Poet As Guest At a Party Of Misfits By MICHIKO KAKUTANI

The New York Times (June 14, 2005, Tuesday)

"The parallels between Michael Cunningham's Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, ''The Hours (1998), and his latest novel, ''Specimen Days,'' will be obvious to even the casual reader. Both novels are haunted by literary ghosts: Virginia Woolf in ''The Hours,'' Walt Whitman in ''Specimen Days.'' Both novels tell three separate stories linked by shared themes and motifs. And both novels feature characters who are essentially variations on -- Shirley MacLaine might say, reincarnations of -- one another.

There, however, the parallels end. Whereas ''The Hours'' overrode its schematic structure with its closely observed characters and intricate musical patternings, ''Specimen Days'' reads like a clunky and precious literary exercise -- a creative writing class assignment that intermittently reveals glimpses of the author's storytelling talents, but too often obscures those gifts with self-important and ham-handed narrative pyrotechnics. Whereas Virginia Woolf and her novel ''Mrs. Dalloway'' were vital touchstones for the stories in Mr. Cunningham's last book, Walt Whitman and his volume of poems ''Leaves of Grass'' feel like afterthoughts grafted onto the tales in ''Specimen Days'' in an effort to lend them extra philosophical weight.

The three novellas that make up ''Specimen Days'' each play with a different literary genre -- the ghost story, the detective story, the sci-fi thriller -- and each takes place (at least in part) in New York City. Taken together, the stories seem meant to make some sort of point about love and death and the precariousness of life -- be it during the era of the Industrial Revolution, the post 9/11 world of terrorism or a future populated by aliens and half-human life forms. All three stories pivot around three central characters: an adult male named Simon, an adult female named Catherine (or Cat or Catareen) and a youngster named Lucas or Luke.

The first tale, ''In the Machine,'' is set in the 19th century and provides a depressing portrait of Manhattan as a sprawling urban sweatshop, populated by the desperate and the poor. Lucas, in this novella, is a 12-year-old boy afflicted with a congenital disorder that has left him ''with a walleye and a pumpkin head and a habit of speaking in fits.'' Simon is his older brother, who has been killed by a machine at the factory where he works. Catherine is Simon's pregnant fiancée. Lucas takes Simon's place at the factory and becomes convinced that his brother's ghost is speaking to him from the deadly machine.

The second tale, ''The Children's Crusade,'' is set in the post-9/11 world and draws an unnerving portrait of New York on edge, haunted by the latest terrorist incidents in which children approach people, give them a hug and then detonate a pipe bomb. Luke, in this novella, is one of those would-be suicide bombers. Cat is a police psychologist tracking the bombers. Simon is her wealthy boyfriend. After tracking Luke down, Cat determines to try to dissuade him from his violent mission.

The third tale, ''Like Beauty,'' is set sometime in the future and draws an apocalyptic portrait of Manhattan as a kind of decadent theme park, where tourists can pay for the experience of being mugged in Central Park. Luke, in this novella, is an 11- or 12-year-old boy who has been left by his mother with a group of Christian evangelists. Catareen is a lizardlike alien, whose entire family was killed on her native planet. And Simon is a ''simulo,'' an artificial human who wants to find the man who created him. Together they make their way across the country and meet up with a group of humans and nonhumans who are planning to take a spaceship to another planet where they hope to start a new life.

In each of these three novellas, Mr. Cunningham demonstrates the ability showcased in his 1990 novel, ''A Home at the End of the World'' -- namely, an ability to create sympathetic characters who are both brought together and estranged from one another by their sense of being outsiders. He also demonstrates in these stories an ability to use genre conventions -- in all their hokey, clanking glory -- to create genuine drama and suspense.

These more appealing aspects of ''Specimen Days,'' however, are completely buried beneath a heavy lacquer of self-conscious writerly effects. Chief among these superfluous devices is the author's clumsy invocation of Walt Whitman in all three stories. Although Whitman is presumably employed to underscore the author's musings about the cyclical nature of existence and the evolving state of America, he never feels like a natural fit for this novel: the poet's optimism and utopian yearnings stand in sharp contrast to Mr. Cunningham's dark view of American life, just as his tireless self-promotion stands in sharp contrast to the solitary, inward lives of these stories' characters.

In fact the use of Whitman's words in these stories feels arbitrary and contrived in the extreme. In the first story the poet's words erupt involuntarily -- like uncontrollable tics -- from the mouth of Lucas, who seems unable to understand their meaning. In the second, they are spoken by the child suicide bombers, who have been taught the verses by the demented woman who trained them as killers. And in the third they have been programmed into Simon by his creator, who says he thought poetry would help his simulos ''appreciate the consequences'' of their actions. Such allusions to Whitman may have been designed to lend added resonance and literary ballast to Mr. Cunningham's stories and to tie them provisionally together, but in the end they amount to nothing but gratuitous and pretentious blather." |

| posted by George Cassiel @ 11:01 a.m. |

|

|

|

|

|

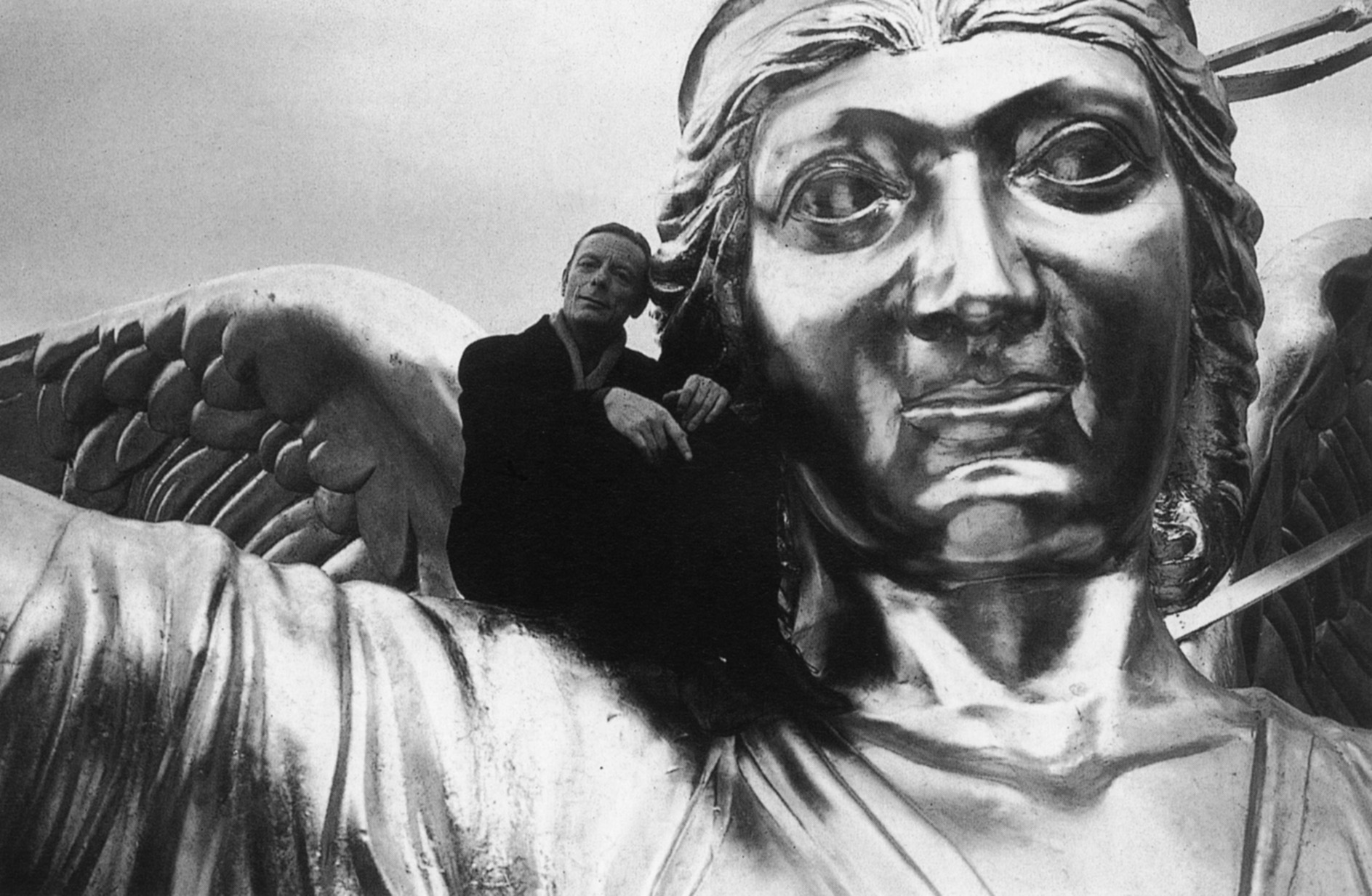

GEORGE CASSIEL

Um blog sobre literatura, autores, ideias e criação.

_________________

"Este era un cuco que traballou durante trinta anos nun reloxo. Cando lle

chegou a hora da xubilación, o cuco regresou ao bosque de onde partira.

Farto de cantar as horas, as medias e os cuartos, no bosque unicamente

cantaba unha vez ao ano: a primavera en punto."

Carlos López, Minimaladas (Premio Merlín 2007)

«Dedico estas histórias aos camponeses que não abandonaram a terra, para encher os nossos olhos de flores na primavera»

Tonino Guerra, Livro das Igrejas Abandonadas |

| |

|

|