| quinta-feira, fevereiro 10, 2005 |

| SEBALD - novidade editorial - mais uma obra póstuma |

Acaba de sair no Reino Unido:

A crítica do Sunday Times de 6 de Fevereiro:

"For someone who died in 2001, W G Sebald has been remarkably prolific over the past few years. Three volumes of poetry, an essay collection and a long work of what Sebald chose to call “prose fiction” (his masterpiece, Austerlitz) have been published in English since his shocking death in a car crash. Some of these books have felt bitty (two of the poetry collections in particular), and one wonders whether Sebald, who exercised a fastidious control over the translation and publication of his work while he was alive, would have consented to their release.

Michel Foucault once asked what limits we place on the definition of a leading author’s “work” after his death: do we publish, for example, Nietzsche’s “rough drafts”, his “journal jottings and crossings out”, or even his “laundry lists”? Such questions are worth posing with regard to Sebald, for he is the most important European prose writer of the past 15 years. It is almost certain that, had he lived longer — he was only 57 when he died — he would have won the Nobel prize.

There are times, it is true, when his narrative technique of fastidious omission leads him to bite off more than he can eschew. And Vertigo (1990), his first substantial work, is an awkward book, afflicted by the tonal wavers of a writer whose voice is breaking to something deeper and more permanent. But The Emigrants (1993), The Rings of Saturn (1995) and Austerlitz (2001) constitute an immense achievement.

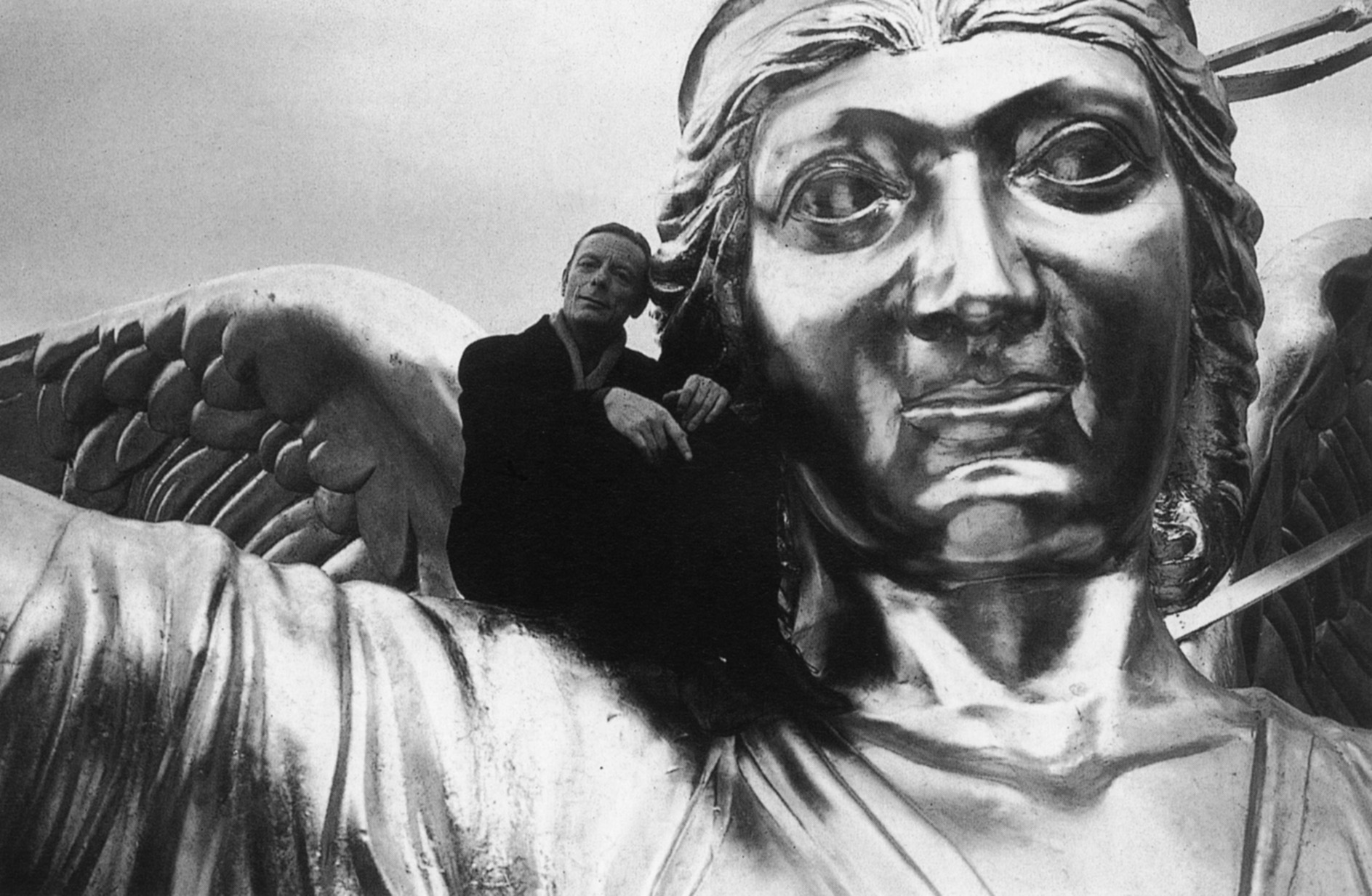

As those readers who have travelled before into Sebald’s greyscale worlds will know, he wrote his books in an uncanny, piebald literary genre that mingled fiction, travelogue and historical anecdote. Scattered among his text are small black-and-white photographs of the places, people and objects that are encountered by his narrators during their journeys.

Sebald’s great theme was mourning, his great mode melancholy and his great proposition was that the past of a culture can work on an individual in the same way as personal trauma. It is for this reason that, in his books, the dead have far greater presence and power than the living. His narrators move through the empty but past-haunted streets of familiar towns in Britain and Europe, following the traces of previous atrocities and sufferings. This may make his books sound oppressive. They are, but in a manner that is exceptionally moving and provoking. His writing has a turbulent power to disturb the sediments of thought and of history.

Many of these same interests and effects are at work in Campo Santo, another posthumous publication. The book comprises four short sections from an unfinished “prose fiction” set in Corsica, which Sebald began and then abandoned in the mid-1990s, along with 12 essays selected from across his career. As such, Campo Santo adds to the asteroid belt of fragments that now encircles Sebald’s completed books. Nevertheless, it seems to me that it will come to be seen as indispensable to an understanding of his work.

The Corsican shards are written in the same long and lovingly decrepit sentences as The Rings of Saturn, and they share with that great book an interest in, among other things, incarceration and deforestation. There are, too, eerily moving digressions on mourning rituals in Corsica, and their transformation by modernity, and a fine meshing of Sebald’s meditations on trees with those of Edward Lear, another melancholic visitor to Corsica’s high Alpine forests.

It is the essays, however, that make Campo Santo such a valuable book. They are widely spaced in time (written between 1975 and 1999) but have been well chosen and are ordered chronologically, so that, as one reads through them, one watches Sebald the academic slowly transforming into Sebald the writer. Authors who write essays on authors they admire often end up describing themselves. This is certainly true of the five exceptional pieces included here on Bruce Chatwin, Franz Kafka (twice), Vladimir Nabokov and Wolfgang Hildesheimer, which act as code sheets by which the enigma of Sebald’s own style can be, if not cracked, at least approximated. From Chatwin, Sebald clearly learns how to use historical story suggestively; Kafka prompts him to meditate on the power of photographs both to charm and to lacerate, while Nabokov teaches him that the “the desire to suspend time can prove its worth only in the most precise re-evocation of things long overtaken by oblivion”.

So many of the insights that occur here can be tilted back to reflect Sebald’s own unforgettable prose, but perhaps none more so than his remark of Nabokov’s Speak, Memory that: “The most brilliant passages in his prose often give the impression that our worldly doings are being observed by some other species not yet known to any system of taxonomy, whose emissaries sometimes assume a guest role in the plays performed by the living." por ROBERT MACFARLANE |

| posted by George Cassiel @ 6:48 p.m. |

|

|

|

|

|

GEORGE CASSIEL

Um blog sobre literatura, autores, ideias e criação.

_________________

"Este era un cuco que traballou durante trinta anos nun reloxo. Cando lle

chegou a hora da xubilación, o cuco regresou ao bosque de onde partira.

Farto de cantar as horas, as medias e os cuartos, no bosque unicamente

cantaba unha vez ao ano: a primavera en punto."

Carlos López, Minimaladas (Premio Merlín 2007)

«Dedico estas histórias aos camponeses que não abandonaram a terra, para encher os nossos olhos de flores na primavera»

Tonino Guerra, Livro das Igrejas Abandonadas |

| |

|

|

Obrigada pela dica.