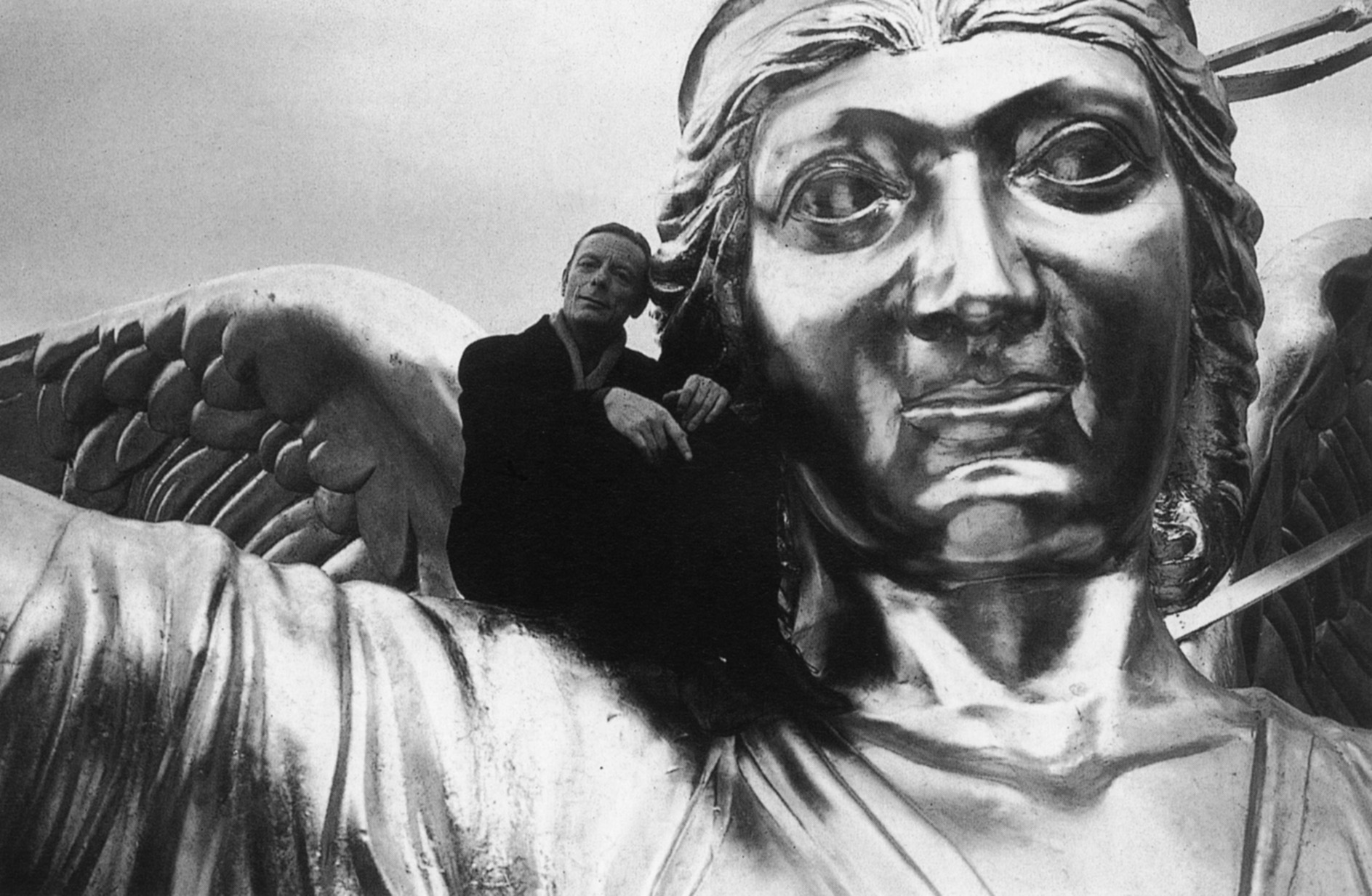

"Seize the Day (1956), Bellow’s most read book, is a sober and deliberate retreat from the exuberance of The Adventures of Augie March. While it has all the surface appearance of a “victim novel,” it has only some of its pessimistic conclusions. The world of this novel is an urban wasteland replete with the sepulchral Hotel Gloriana. Out of work as a salesman, and estranged from his wife and children, Tommy Wilhelm finds himself nearly penniless in early middle age. As a young man he has rejected his father’s profession, medicine, tried out for a career in Hollywood, been tricked by a phony talent scout, ended up in sales and lost his district due to his boss’s nepotism. He is Bellow’s version of the classic schlemiehl of Yiddish folklore. In the dreadful Hotel Glorianna, amidst the aging capitalist fathers of a previous era, Tommy becomes aware that he has failed to fulfill their notions of masculine achievement. However, while he has failure to accomplish the American capitalist dream, he appears to be cultivating alternate values of love, feeling, compassion, and non-competition. Ultimately Tommy is conned not only out of his remaining cash, but also almost out of human hope as well. Some reviewers have called Tommy Wilhelm pathetic, while others called him heroic. Some were dismayed with book’s tight organization and seemingly modern aesthetic. Others praised it for its concentration, intensity, and focused crescendo. Years later, Bellow told interviewer that he was appalled at the philosophical immaturity of Augie March and wrote Seize the Day in an attempt to transcend its effusive and emotional limitations. It was possibly written before The Adventures of Augie March at the same time as the first two “alienation” novels, though Bellow has never more than hinted at this. Despite its alienation formulas, many critics read the novel as counterpointing death and despair with psychic renewal and spiritual survival. They suggest that despite Tommy’s experience of victimage, mass society, absurdism, and modernist metaphysics, Bellow is clearly shaping a fiction of hope. His devilish morality play figure, Dr. Tamkin, who spouts absurdist philosophy, mangled Freudianism, alienation ethics, and cheap nihilism to Tommy, is presented as a charlatan and a physical grotesque. While Tommy longs for accessible, sensible truths, Tamkin assures him there are only crooked lines. When Tommy asks him where he gets his ideas from, Tamkin becomes the butt of one of Bellow’s funniest jokes: “I read the best of literature, science, and philosophy,” he says. In his carpe diem sermon, in which Tamkin tells Tommy to take no thought for tomorrow because the past has no value and the future is an impending nightmare. In spite of his wife’s, his employer’s, his father’s, and Tamkin’s betrayal of him, Tommy, in this reading seems naively determined to “recover the good, things, the happy things, the easy tranquil things of life [. . . ].” Things were too complex, but they might be reduced to simplicity again.” His final emotional climax, such critics argue, is not bitterness at betrayal, but the achievement of love for all the lurid, imperfect people like himself whom he discovers in the underground subway in Chicago and in the funeral parlor. It is also the novel in which the seeming-orphanage of Joseph, Asa, and Augie, develops into an in-depth treatment of the failure of a father-son relationship. Dr. Adler, the highly successful, but narcissistic, arrogant old surgeon, spurns his son’s emotional pleas for nurturance and financial help. Embarrassed by Tommy’s repeated failures, he lies to his friends in the retirement home of his son’s financial prowess. Dr. Adler clearly refuses to validate any other form of masculine achievement other than financial. Into his character Bellow invests hostility and moral reproach.

Though Tommy has failed at marriage, fatherhood, money, and status, Bellow has given him all the right instincts for spiritual survival and social contract as he identifies with the countless unknown others with whom he shares the human plight. It is knowledge, Bellow insists, that resides within the sufficiently humanized soul, and requires no elaborate acquaintance with either philosophy or the world of crass commerce. In this book, Bellow also continues his protest against destructive, American capitalist codes of masculinity which eclipse the contemplative and the poet whose truer achievements will be sensibility and filiation. Significantly, contemplative and poet alike are conceived as male in the Bellow canon. " |